“Oh no, it’s the retrospective time!”

This cry for help is not uncommon, I’m afraid, among practitioners of Scrum. That is a shame. For me, this meeting is the climax of the scrum framework – this is the place where we get better. The discussions can get very deep and very meaningful. I would like to show here how to move from the statement appearing in the title of this paragraph to “Oh boy, it’s the retrospective time!”.

Timing

The retrospective is scheduled to take place at the very end of the sprint. For many teams, this is the time when all their development efforts from the entire sprint culminate. The thought of stopping at this time their intense activity toward a boring (see later about that) meeting is irrationality itself. And so, around 5 minutes prior to the time of the meeting people get the cancellation email, or out of habit the meeting is plainly ignored.

Indeed, it doesn’t make sense to stop everything abruptly just like that, at the peak of the sprint’s activity.

What can we do about this?

I believe that the problem is not with the timing of the retrospective, but rather with the dynamics of the sprint. What does it say about the quality of development if everything ends at the last minute? Will there be time for proper testing? Will there be time for proper reviews? Will there be time for proper feedback?

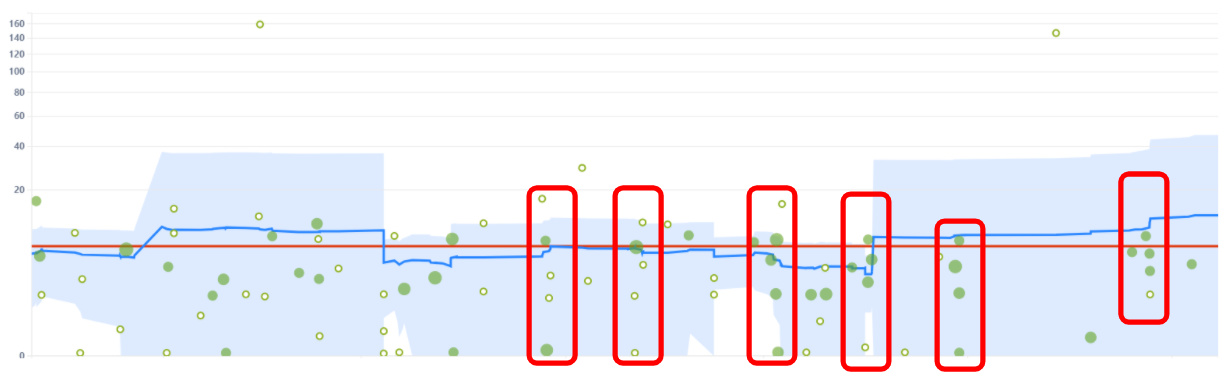

Here is Jira’s control chart of a team that ends most of the work at the sprint’s end. I’ve circled columns of dots. Each dot is a development item ending on the X-axis date. The height of the dots is how long it took to complete. You see that items started at different times but ended together. This is the phenomenon known as end-of-sprints-pressures.

This is something to talk about in a retrospective! Try getting items to do all along the sprint and you will both reduce the pressure off the team and have time for retrospectives and other important (but not as urgent) activities.

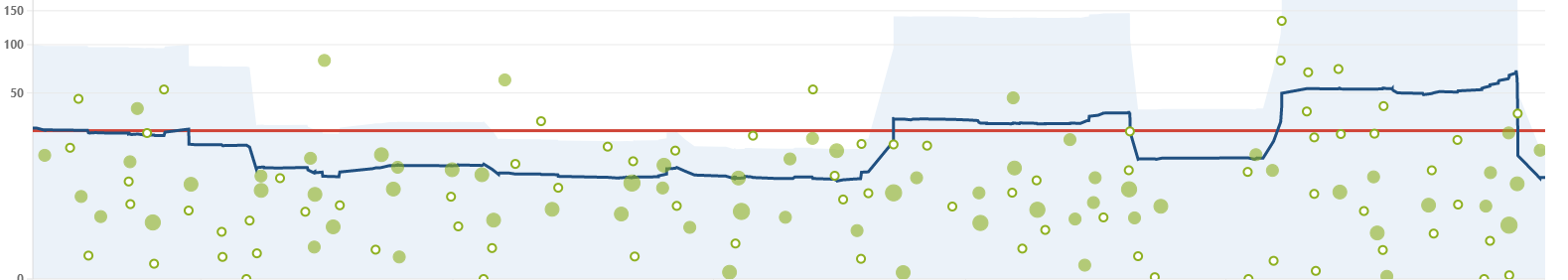

The below team works like that:

Safety

Many retrospective meetings are a good place for self-contemplation, as they are very quiet. The scrum master says some words to open the meeting and then it’s all mum’s words. No one is saying anything.

Is it so quiet because everything is perfect? Usually, that will not be the case. Many times people don’t talk because (1) they are afraid that anything they say will boomerang back to them and (2) they don’t believe anything can really change. We’ll talk about (2) later here.

A retrospective meeting is a very delicate meeting as we talk about how we do things, a meeting where we try to take a look at ourselves from the outside.

People will talk if they feel safe. In many teams, people don’t feel comfortable talking about what they did, and what others did, especially the things that could go better.

How can we change that?

The first thing that we need is patience. It takes time to build trust. People will feel safe if they see consistency in behavior for a long time. What behavior? See here for a few suggestions.

If you want people to talk about what they can do better, start with yourself. A scrum master showing vulnerability is someone you can trust. Talk about what you can do better. Talk about things you did that didn’t go well. Ask team members to suggest improvements. Try adopting these.

Lead by example: act as you expect the team to act. That would be a great first step.

Next, don’t talk about what went wrong. The language is “what could go better”. That’s looking at things from a positive perspective. We are not looking for people whom we can blame. We are looking for ideas for things to improve.

When someone talks about something that didn’t go well, don’t press on why they were wrong, but rather how it can work better the next time.

Last, do not use things said in the retrospective outside the meeting. The only purpose of this meeting is to improve. If people will hear things they said used against them or against others in some other context, they will not talk.

People need to feel safe: lead by example, think positively, and focus on improvement.

Topics for discussion

What do we talk about? We have the time, we feel safe to have an open discussion, and still, we can hear the air flowing from the air conditioning system.

A good starting point for discussion is whether the team achieved the sprint goal and why. My experience shows that from that point a very good conversation follows. For example:

The only issue with this suggestion is that many teams don’t have a sprint goal, and that’s something worth handling.

The sprint goal is a statement that can be answered with Yes or No at the end of the sprint. This statement is formulated by the entire team during sprint planning. You look at the scope of stories that is your forecast for the sprint and you try to bring it to one statement. Once you have that statement you ask yourself whether your forecast serves that goal.

The goal is used throughout the sprint as a guiding star to show the direction. If you don’t have a goal, you don’t have a direction, you have a bunch of development items, and then at the retrospective, it is not clear what did we try to achieve.

Talking about the goal in the sprint retrospective creates a very good discussion. Did we meet the goal? Yes – what are the good things we did?

No – what could go better next time?

Experimentation

As stated above, one of the reasons people don’t talk during retrospectives is that they don’t believe anything will change. A very good way to have things change is by experimenting.

Many times during retrospective meetings we understand something should be changed. Reaching a decision to actually change something is not easy – what will be the consequences? Can it hurt us? A good approach to this is through experimentation. Instead of getting big decisions let’s agree on a small, pinpointed experiment.

For example, I believe in pair programming. Usually when I mention this people talk about it but it is very difficult to get a decision on it. Then I say – “guys, I am definitely not suggesting that starting tomorrow all your work will be done in pairs. All I suggest is that you give it a chance and try it out. Why not have two guys pair for 2 hours on the next sprint? Let’s talk about it in the next retrospective and see what came out of it”. It is much easier to get a decision in two hours for the next sprint than a total change in the way we work.

Following Through

Deciding on experiments is good but we get the real value when we follow through. And what better place than the retrospective meeting?

A good time to check on our experiments is immediately after the discussion about meeting the goals. Many times you will find that your experiment contributed (hopefully positively) to making the goal.

At the end of the discussion about the experiment we did comes the question – what next? Should we set up another experiment? Should we expand the experiment? Should we back away from it?

Regarding our experiment: we said we will try pairing. The two developers involved said it worked great (it usually does, by the way. You should give it a chance. Maybe start with two guys pairing for an hour or two?) We now want to continue with this experiment and ask all developers to have at least one hour of pairing with another developer in the next sprint. We will use the daily meeting to look for good pairing opportunities.

“Oh boy, it’s the retrospective time!”

Good retrospectives march you forward professionally, as a team, and as an individual. This is your chance to zoom out of the day-to-day and look at the big picture. To make it happen you need to have the time, let people feel safe, and have good topics for discussion – like the sprint goal. Deciding on experiments and following through on them is the bottom line that makes people trust the process.